A previous post highlighted an

investment

selection process you might consider if you’re thinking about farming

dividends.

It’s helpful to understand

the investing style or philosophy you want to follow before you delve into a

specific process.

Below are several items for you to consider as an

investor. How you relate to each

individually and in aggregate help shape your investment style which influences

any process you decide to use in selecting investments. In general, you should align these factors as

much as possible before you move down the investment path.

|

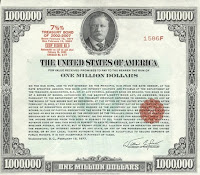

| Dividend Cash Flow |

Cash Flow vs Value

Appreciation: Some investors

preference consistent cash flow while others pursue value appreciation of their

investment.

The former are less

concerned with the size of a brokerage account than with the quantity and

reliability of funds dispersed in the form of dividends (cash flow).

The latter want to see their holdings grow in

value as much as possible between now and whenever they elect to sell and reap

the proceeds.

Risk Tolerance: Your propensity to tolerate risk influences

your investment path. You may wish to

think otherwise, but over long investment horizons, risk tolerance misaligned

with investing style isn’t sustainable.

In such situations, you can experience a level of cognitive dissonance

seriously affecting investment performance.

For instance, fancying yourself an aggressive growth investor because

that’s the style du jure, when you’re averse to high levels of risk, may leave

you financially and emotionally exposed to losses from which you can’t recover.

Desired Return: The rate of return you desire from your

investments also influences your investing decision. High rates of return often correlate with

higher than average investment risk.

Consequently, desired return is frequently married to risk tolerance

when weighing investment styles. If you

wish to double your money in 12 months, you’ll likely have to take outsized

risks to do so. If you can’t tolerate

that kind of risk, your desired return of twice your original investment within

a year isn’t practical and should be reevaluated.

Ability to Learn: If you stop learning, you stop growing. If you stop growing, you start dying. While the universal truth of this statement

may be argued, it’s often true enough of investing that you should pay

heed. Investors, whether passive, value,

growth, technical, fundamental, or any other, who fail to continuously learn

lock themselves into yesterday’s investing environment while today’s ecosystem

quickly marches forward. Imagine using

computer technology from 1998 to run your business in 2018. Failure to upgrade and retrain on new systems

means a competitive disadvantage to your firm.

Failure to upgrade, retrain, refresh, and continually expand your

investing knowledge leaves you at a decided and dangerous disadvantage. Do you need to be aware of all the latest

advances in technical analysis or high frequency trading? No.

Should you keep abreast of economic, industry, and business trends? Yes.

Business Interest: Many investors don’t consider their interest

level when deciding when, where, or how to invest. It’s just something people “do” because their

parents did it, they’re required to do so through a company plan, they feel it’s

necessary for social acceptability reasons, or they fear destitution in

retirement. None of these constitute the

type of business interest needed to be a successful investor. Rather, business interest means being

genuinely interested in business at some level.

If you’re not, you won’t take the time to learn, even if you’re

eminently capable of learning all that’s required.

Time Horizon: The single largest determinant of investment

success is time.

The more you have in

which to invest, the better you’re likely to do.

Whether you’re looking at the long-term trend

of stock markets or considering the strength of

compound

investment growth time is your friend.

As with friends, time should not be taken for granted nor its benefits

wasted.

Invest as early as you can.

Continue investing regularly along the

way.

Keep at it for the duration.

If you do, you can generate a substantial return

over time, irrespective of your investment style.

How do these considerations fit within the Dividend Farming

framework?

Cash Flow vs Value

Appreciation: The Dividend Farmer focuses on cash flow. As with agricultural farmers, it’s better to

harvest crops on a regular basis while working continuously to grow the crop

yield. Having your land appreciate in

value is nice, but you can’t pay the bills with appreciated land unless you

borrow against it, which adds additional risk and increases your costs, or sell

it, in which case it’s no longer yours.

The same holds true for dividend farming. The goal is to be able to harvest as needed

while growing the yield over time. The

best part is that if a dividend harvest isn’t needed at a particular time, the

yield can be reinvested to gain more “ground” along the way compounding your

return.

Risk Tolerance: Dividend farming takes a value investing perspective,

like Benjamin Graham and later Warren Buffett.

Consequently, it’s fairly risk averse.

If you can tolerate high levels of risk, particularly over extended

periods of time, you may find other investing styles a better fit.

Desired Return: Dividend farmers are concerned with steady

and predictable if unspectacular rates of return. While farmers enjoy bumper crops, they’re not

enthusiastic about a bumper crop in one year followed by drought and pestilence

the next. As a result, shouldering higher

than average levels of risk to obtain a significant rate of return isn’t of

interest to a dividend farmer. Instead, one

should focus on the continuous compounding of the investment crop to do the

work while maximally leveraging time. Downside

is minimized with the approach. However,

the possibility of enormous, newsworthy rates of return are normally given up. Dividend farmers are ok with that.

Ability to Learn:

Farmers are always learning. The science of farming, weather, technology,

and markets never stop and neither do they.

The same goes for Dividend Farmers.

If you’re not regularly reviewing your investments and their activities,

learning about markets, or trying to understand the events that influence your

investments, you’re limited to serendipity for investment successful.

Business Interest:

In line with ability to learn is business interest. Nearly everyone is capable of learning. We learn something new nearly every day. However, business interest means channeling a

portion of those learning capabilities into the investing arena. If investors aren’t interested in learning

about their investment style, their investments, or the market in general, they

will not develop the knowledge base to be successful. In such situations, throwing a dart at a

board may be the best an investor can hope for unless he’s willing to put all

his trust into an investment advisor.

While this is not inherently a bad thing, dividend farmers are DIY types. If you’re not, then farming dividends may not

be the path for you.

Time Horizon: Time

is the single greatest factor affecting investment success.

In total, it’s more powerful than savings,

selection, or happenstance.

It offers

new investors the chance to learn without causing unrecoverable investment

problems.

Time allows investments to

compound taking advantage of one of the greatest powers in the investment world

– compound interest.

Risk mitigation

through time to reach desired investment goals becomes possible.

Doubling your money in 12 months requires a

great deal of risk, but doubling it in 10 years requires a 7% return which is

roughly the average long-term rate of return of the stock market.

|

| Dividend Tree |

Dividend farmers employ time to achieve their

investment goals. The best way to maximize

time time is to start early. It’s been

said the best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The next best time is today. Don’t wait, plan a dividend tree today.

The

thoughts and opinions expressed here are those of the author, who is not a

financial professional, and should not be considered as investment

advice. The information is presented for consideration and entertainment

only. For specific investment advice or assistance, please contact a

registered investment advisor, licensed broker, or other financial professional