There’s a world of difference between average annual growth and

compounded growth. The first figure is referenced by sellers peddling

their wares; the second by investors with a clue. For instance, one

financial pro may direct a buyer toward a mutual fund sporting an average

annual growth rate of 12% while another advisor might offer a product with an

8% compound growth rate.

|

| Control what you can control: Compound interest. |

People who aren’t informed, but happen to know that 12 is

greater than 8 will invest in the vehicle with the 12% return while foregoing

the item that “only” has an 8% figure associated with it. All other

things being equal, this is a mistake. The reason is related to the post about the Rule of 72.

Here’s a simple example…

A stock is purchased for $10. At the end of year 1 it has

appreciated to $20. This change represents an annual growth rate of

100%. However, at the end of year 2 the stock’s price has fallen back to

$10 representing a 50% decline in value. The average annual return for

the two years is therefore (100% -50%) / 2 which equals 25%. However, you

have the same $10 stock you started with 2 years earlier. Doesn’t

feel like 25% growth, does it?

Conversely, the compound growth rate of the stock would be 0%

which accurately reflects the $0 change in value during that 2-year period.

Let’s work the math the other way. If that same $10 stock

appreciates at a compound rate of 8% over 2 years it would be worth $12.10 at

the end of the period or $10 X [(1+.10)2-1]. The $2.10 change

in value over the investment horizon represents an average annual growth rate

calculated as ($2.10 / $10) / 2 years or 10.5%.

In both examples, the average annual growth rate is higher than

the compounded growth rate. The difference between the two calculations

is fantastic for marketing and sales purposes, but not so hot if you’re buying

because one percentage figure happens to be larger than another.

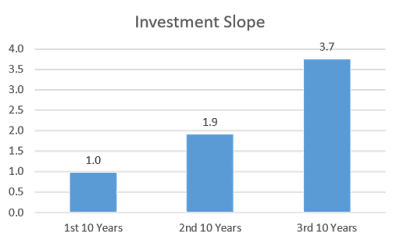

What does this difference mean over a longer investment

horizon? Let’s assume you start investing with $1,000 you received as a

graduation gift from high school. You have a choice between investing it

for 10 years at an average annual growth rate of 10% or a compound growth rate

of 8%. At the 10% average annual growth rate, there will be $2,000 in

your account at the end of 10 years. You will have doubled your money.

However, if you invested it at an 8% rate compounded annually

you would have $2,158.92 earning $158.92 more than you would have with the

alternative. Maybe this doesn’t sound like much of a difference to you, but

when you extend the math out to 20, 30, or even 40 years of an investing life,

the delta in ending values is significant.

As I’ll mention in a related post, the Rule of 72 is based upon

a compound growth rate; not an average annual growth rate or average return.

There are investment advisors out there touting average annual growth rates and

using them in relation to the Rule of 72. Whether this is done out of

ignorance or avarice is debatable but in either case it’s wrong and you should

be aware. Caveat emptor, indeed! It’s better to understand in

advance what’s going on than find out years later and thousands of dollars

stranded on the table that you didn’t know your financial math when you plunked

down your money.